Video games are often thought of as a strictly visual media. They are frequently assessed by their ability to create pictorial representations of virtual worlds, and their graphical fidelity is increasingly scrutinized as an important trait. Gamers want their games to look pretty, and art direction and character design are amongst the first aspects of a game that draw potential buyers to it. Sound design and music are given mention as well, but the physical movements required to play games are rarely brought into discussion. Upon further deliberation of the physical nature of games, it becomes clear that playing video games and dancing share considerable similarity.

At its heart, dance is coordinated movement that produces a spectacle. It lasts only an instant, and is the act of showing events in motion. In order to learn a dance, the proper choreography must be internalized within the dancer, so that s/he may reproduce it later. In order to begin the learning process, the dancer starts with the basic step, and subsequently adds more complicated gestures to be utilized as the basics become more natural. Dance styles must be broken down into simple movements in order to be understood by a beginner. The same is true with video game players. Games–which typically employ short tutorials in the onset–, seek to teach the player the necessary hand movements needed in order to access the entirety of the game’s form. Using Dying Light as an example, the game program starts by telling the player how to perform simple actions like moving the avatar and controlling the camera. Soon after, the basics of jumping over objects, climbing up the terrain, and ducking under suspended beams are shown in a sequence in order to replicate the necessary actions using the controller that will be implemented in the future. It is in this moment that the player is learning choreography that will be harnessed in increasingly difficult progressions. Here, the game developer or the game program acts as the choreographer that teaches the player the hand movements needed in order to successfully play. In any game, players are required to employ the necessary choreography in order to find success and experience the entirety of the game. As the game gets more difficult, it assumes the player has overcome the ‘basic step’ and is ready to perform more complicated actions on the controller. Ultimately, just as dancers must master a dance incrementally by manifesting basic steps before incorporating rigorous and rapid action, so must gamers learn the essential hand movements on the controller so that they may continue to experience the game.

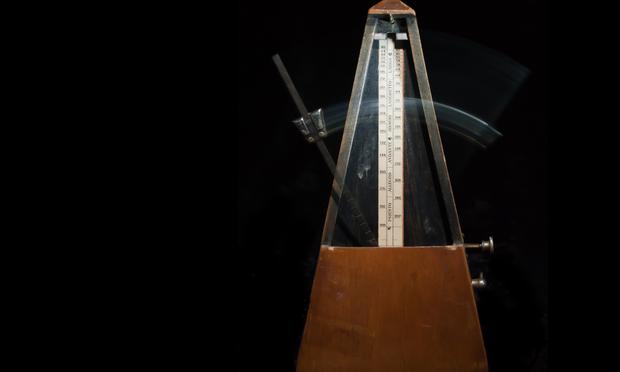

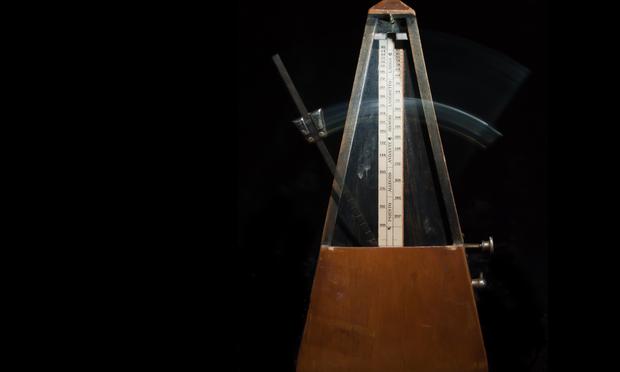

The game software acts as a choreographer, but it also dictates the rhythm of play. Continuing to use Dying Light as an example, the game allows the player an infinite amount of time to learn the basics of the dance before letting him/her into the game world. Yet, as players continue through the game, they are called to perform the hand motions necessary for their survival at varying points in time. These moments of required action make up the rhythm of the game. Players are given time to explore and hone their manual dexterity in the earlier sections of the game, but as the game progresses, it demands the players to perform new sequences of choreography with the controller and sustain them for longer, often in quicker succession. By the end of the game, the time allowed for relaxation is much shorter, and the rate at which the game demands physical execution comes more frequently and lasts longer. This directly mirrors a dance routine, which begins by showing first the basic movements of the dance, and culminate in a crescendo of flourishing movement in which complicated moves are executed in a rapid and extended manner. Both games and dance share a rhythm which dictates when physical movements of the body must be executed.

The most obvious comparison to be made between gaming and dancing is the requirement of physical dexterity. When watching a dancer perform, the visuals produced by their bodies may be impressive in their own right, but what commands admiration is the execution of physical skill. Audiences see the gestures and body movements and can imagine the difficulty they would be greeted with if they tried to emulate them. The external show is appreciated because the audience has knowledge of the internal tension present in the dancer. The same can be said about game skills. When scores of people gather around a screen to watch the worlds best fighting game players at EVO, it is not to see virtual kicks, uppercuts, and jabs. It is to witness the execution of large sequences of combos, or to observe the breakneck physical, reaction speed of the world’s best. When spectators view impressive fighting play, or see someone get through the most difficult Guitar Hero songs with perfection, the admiration is not brought on by the sight of colored circles exploding into fire. It is created from the knowledge of the intense skill, discipline, mental focus, and rehearsal needed to execute such physical skill. Just as we appreciate the dancer because we know we could not emulate his/her moves, we appreciate game skill because of the awareness of the difficulty that awaits us if we were to reproduce their performance.

Lastly, both performing dance and playing games function within ‘appropriated time’. This is defined as time that forgets itself, no longer counts, feels abundant, and is structured around the rhythm of play rather than social functions or natural, chronological time. When one dances, they think not of time, only of executing actions in the moment. Just as when players play games, they often forget about ‘real’ time, and instead focus on the movements and activity associated with gameplay.

Dance and gaming share a large similarity. Besides both struggling to find academic acceptance and study–dancing wasn’t considered by academia until the 1980s–, they are physical activities that lack permanence, but are enjoyed only in the moment of performance. They require knowledge of basic physical choreography that is employed in ever-increasingly difficult sequences. The rhythm of dance and the rhythm of the game dictates when dancers/gamers must perform their progressions of physical movement. And like dancers, we marvel at video game skill not only because of the visual result, but because we know the tension behind execution would be impossible for us to emulate. Though video game discourse typically centers around the visual aspects of the medium, it is an intensely physical activity. Now, go forth and continue to dance with your games.

This article draws from ideas laid out by Graeme Kirkpatrick in his book Aesthetic Theory and the Video Game, more specifically chapter 4.